Health and safety continues to improve around the world year on year, with fatality and injury numbers gradually decreasing. Recent changes include the introduction of the Health and Safety at Work Act in New Zealand and stricter sentencing guidelines in the UK. But health and safety wasn’t always a priority for businesses.

So when did the idea of workplace health and safety start to be taken seriously and how has it progressed since the beginning?

The Industrial Revolution 1760 – 1800s

Before the Industrial Revolution began in 1760, it was the norm to make a living through agriculture or the making and selling of products from the home. With new developments in machinery and manufacturing processes, Britain, followed by parts of Europe and the US, began moving towards a society fuelled by mass production and the factory system.

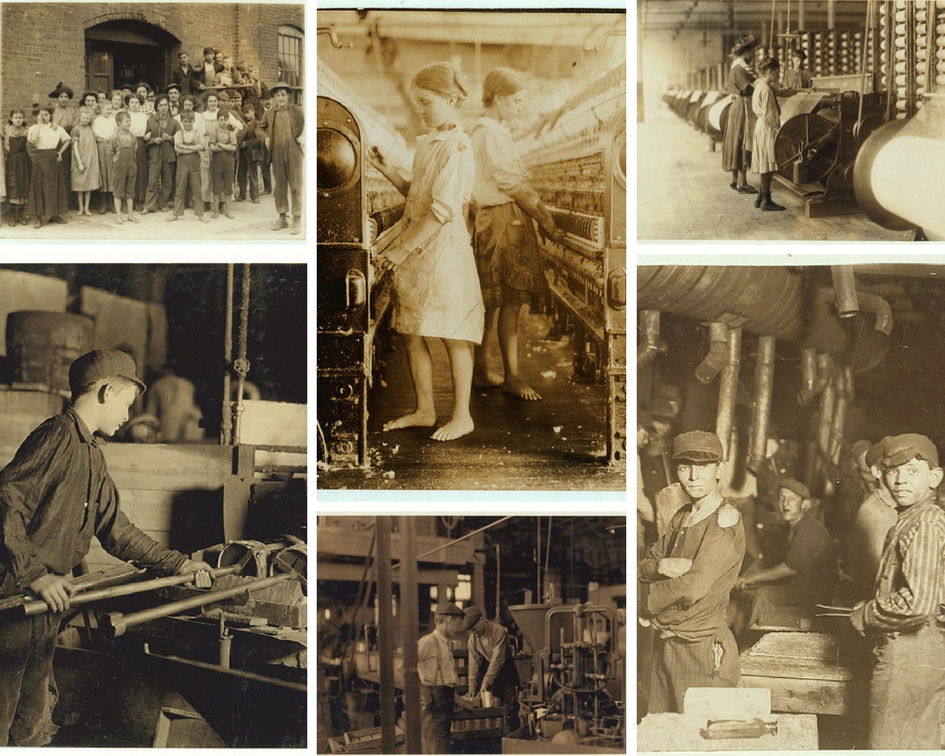

People flocked to the cities for work where there were increased opportunities for employment in the new mills and factories. The vast number of people looking for work, and the need for cheap labour, led to poor pay, hazardous factory conditions and an increase in child labour. Hours were long and conditions dangerous, with many losing their lives at work.

Work was particularly dangerous for children who would work from as young as 4 and sometimes over 12 hours a day. Many were used to climb under machinery which would often result in loss of limbs while others were crushed and some decapitated.

Girls working at match factories would develop phossy jaw from phosphorus fumes, children employed at glassworks were regularly burnt and blinded, while those working at potteries were vulnerable to poisonous clay dust. A lack of health and safety also meant that many children developed occupational diseases such as lung cancer, and died before the age of 25.

The Factory Act 1802

An outcry over child labour conditions led to factory owner, Sir Robert Peel, introducing the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, commonly known as the Factory Act.

The Factory Act applied to all textile mills and factories employing three or more apprentices or twenty employees and required factories to;

- Have sufficient windows and opening for ventilation

- Be cleaned at least twice yearly with quicklime and water

- Limit working hours for apprentices to no more than 12 hours a day (excluding time taken for breaks)

- Stop night-time working by apprentices during the hours of 9pm and 6am

- Provide suitable clothing and sleeping accommodation to every apprentice

- Instruct apprentices in reading, writing, arithmetic and the principles of the Christian religion

While limited to a small portion of the workforce and with limited enforcement, the Factory Act is generally seen as the beginning of health and safety regulation.

The introduction of factory inspectors 1833-1868

Workers tired of spending over 12 hours a day in the factories, began a movement to reduce working days to 10 hours, known as the “Ten Hours Movement”. Pressure from the group led to the Factory Act 1833.

The Act extended the 12 hours working limit to all children and included woollen and linen mills. Perhaps the most important development however, was the introduction of factory inspectors. The inspectors were given access to the mills and granted permission to question workers. Their main duty was to prevent injury and overworking of child workers but were also able to formulate new regulations and laws to ensure the Factories Act could be suitably enforced.

Despite only four inspectors being appointed for approximately 3,000 textile mills across the country, they were able to influence subsequent legislation relating to machinery guarding and accident reporting. A growing public interest in worker’s welfare, influenced in part by popular writers such as Charles Dickens, saw inspector numbers grow to 35 in 1986. The type of workplaces they were able to enter also grew to cover the majority of workplaces.

The introduction of ‘duty of care’ 1837

On May 30th 1835, Charles Priestley suffered a broken thigh, dislocated shoulder and several other injuries after a wagon cracked and overturned due to overloading by his employer, Thomas Fowler.

Priestly spent nineteen weeks recovering at a nearby inn, which cost him £50 (a considerable amount at the time). Priestly sued Fowler for compensation relating to the accident – the first documented case of an employee suing an employer over work-related injuries. The jury awarded Priestley £100 in a landmark case which established the idea that employers owed their employees a duty of care.

However, an appeal of the case established that the employer is not responsible to ensure higher safety standards for an employee than he ensures for himself.

Safety regulations increase 1842-1878

Several acts introduced over the next 36 years, saw protection towards women and children strengthen. Women and children were prevented from working in underground mines, the use of child labour to clean and maintain moving machinery was stopped, and a 56-hour work week for women and children was introduced.

The Employer’s Liability Act 1880

In an attempt to correct the doctrine of Common Employement established following Priestly v. Fowler, the Employer’s Liability Act enabled workers to seek compensation for injuries resulting from negligence of a fellow employee.

The act states that any worker or his family, are entitled to compensation for injury or death caused by a defect in equipment or machinery or negligence of a person given authority over the worker by the employer.

The Workmen’s Compensation Act 1987, later removed the requirement that the injured party prove who for the injury, and are instead required only to prove that the injury occurred on the job.

A continued increase in acts and reforms 1880-1973

Health and safety continued to flourish, with a number of acts and reforms improving upon health and safety regulation across the country. Employers were required to provide safeguarding for machinery, the legal working age was gradually raised, and more and more inspectors were appointed across industries.

1878 even saw the first safeguarding put in place for those working in the Agriculture industry, in regards to equipment, machinery and poisonous substances

Occupational Safety and Health Act 1970

Much like in the UK, mass production, the use of machinery and the availability of cheap labour, meant that health and safety was not always a major concern. In fact, it was cheaper to replace a dead or injured worker than to implement health and safety measures.

However, growing concern following World War II, soon led to the signing of the Occupational Safety and Health Act into US law. The legislation’s main goal was to ensure employers provide employees with a work environment free from hazards including exposure to toxic chemicals, excessive noise levels, mechanical dangers, heat or cold stress and unsanitary conditions.

The act also led to the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Health and Safety at Work Act 1974

In the same year as the Occupational Safety and Health Act was introduced, the Employed Persons (Health and Safety) Bill was introduced in the UK. However, debate around the bill generated a belief that it did not address fundamental workplace safety issues. Following the passing of the Act in the US, a committee of inquiry was established in the UK.

It wasn’t until 1974 that the Health and Safety at Work Act was passed. The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 was a revolutionary piece of legislation that forms the basis of health and safety legislation across the world today.

Unlike previous acts in the UK, the Health and Safety as Work Act encompassed all industries and employees. The Act places responsibility on both the employer and employee to ensure the health, safety and wellbeing of individuals across all workplaces, and members of the public who could be effected by work activities.

The act also lead to the creation of the UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE), which was put in place to regulate and reinforce UK legislation.

Changes in the workplace as a result of the Act, saw an incredible 73% reduction in the number of workplace fatalities between 1974 and 2007. Non-fatal injuries also fell by 70%.

2019

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, still forms the basis of workplace safety law in the UK, and went on to influence legislation in Europe, New Zealand and other parts of the world. While the principles have largely remained the same, the Act continues to see updates and reforms alongside the evolution of the workplace and new health and safety challenges that arise.

Fortunately, the explosion of the internet and rapid developments in technology, has made managing health and safety in the workplace more efficient then it has ever been before.

While countries around the world continue to work to reduce workplace accidents and fatalities, StaySafe are excited to be a part of the expansion of safety technologies, used to increase workplace safety and businesses efficiency.

Find out more about our safety solutions here